______________________________________

Tucker’s Cover

January 25, 2026

# 1750

_________________________________________________

Thoughts on Global Levity Day, from Dom’s Porch

Start your celebration the night before by taping a “Smile” reminder to your bathroom mirror. You’ll see it first thing.

When you wake, respond to last night’s posted exhortation by forcing a smile before your feet hit the floor.

Wearing that smile, however thin, shuffle to the bathroom preparing for a battle with your own face: time to shave, because, apparently, stubble doesn’t take weekends off.

Rinse the last of the shaving cream from your face pretending it’s invigorating and not an act of survival.

Brush your teeth, still smiling, as though auditioning for a toothpaste commercial.

Pick out today’s outfit, perhaps dressing in front of the TV accompanied by the soundtrack of whatever catastrophe the local news is offering up today.

Fumble with your hair until shrugging in acceptance, muttering “fine,” a generous verdict at best.

Still smiling, admire your reflection, hoping your facial expression doesn’t look more appropriate to a hostage negotiation than a mood booster.

Make your coffee with the solemn focus of someone performing minor surgery.

Imbibe the caffeine, hoping it will form a smile when your mouth muscles cannot.

Close your apartment door behind yourself and step out to face the happy world.

Welcome to Levity (Belly Laugh Day — Jan 24)

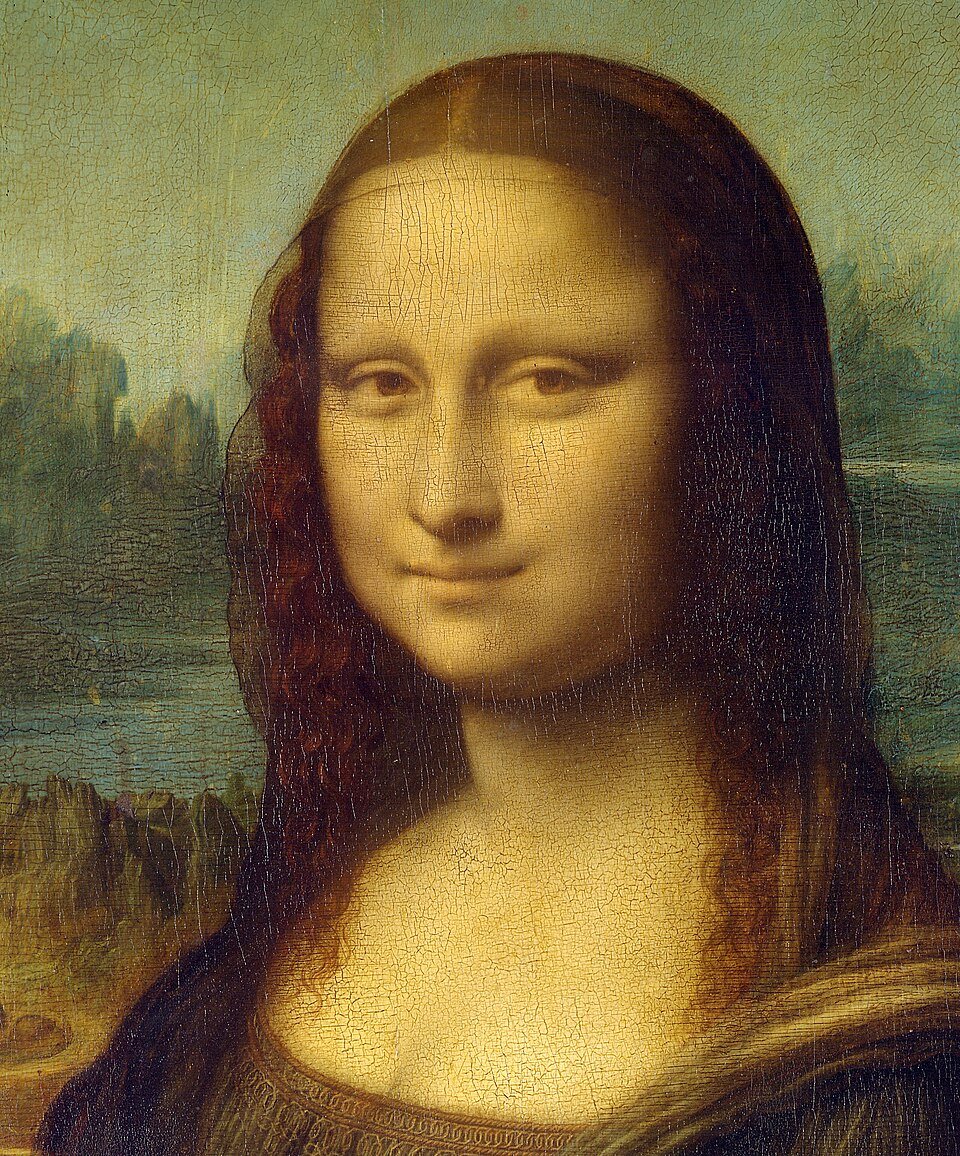

The Mona Lisa is a half-length portrait painting by the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described as "the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, [and] the most parodied work of art in the world." The painting's novel qualities include the subject's enigmatic expression, monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism.

_________________________

More Thoughts from Porch

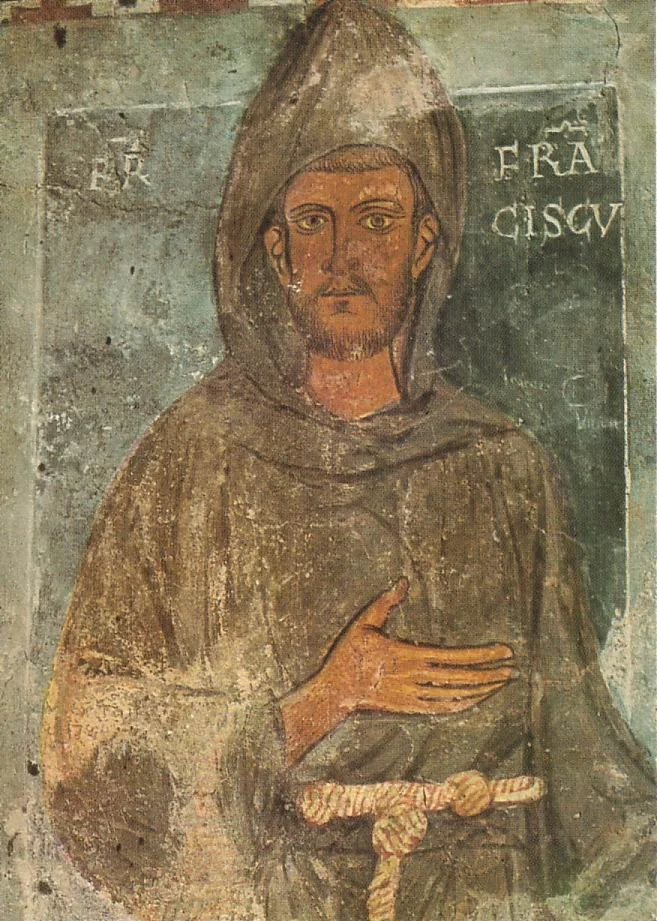

In the course of his spiritual development Richard Slavin (Eventually Radhanath Swami) spent some time in Assisi tracing the life and works of St. Francis of Assisi.

The oldest surviving depiction of Saint Francis is a fresco near the entrance of the Benedictine abbey of Subiaco, painted between March 1228 and March 1229. He is depicted without the stigmata, but the image is a religious image and not a portrait.[6]

Anonymous - da web

St. Francis (Subiaco, Sacro Speco)

Radhanath Swami has often spoken of St. Francis of Assisi as one of his deepest inspirations, especially in the years before he formally embraced the bhakti tradition. While the search results didn’t surface direct material on this connection, his well‑known teachings and memoirs make the relationship clear.

St. Francis represents, for Radhanath Swami, a universal archetype of devotion — someone who lived with radical simplicity, humility, and love for all beings. In The Journey Home, he describes encountering Franciscan ideals during his travels and feeling an immediate kinship: the saint’s poverty, compassion, and reverence for nature mirrored the bhakti values he was slowly discovering in India.

What moved him most was St. Francis’s fearless tenderness — the ability to see God in every creature, to serve the poor without hesitation, and to surrender ego completely. Radhanath Swami often cites him as proof that genuine spirituality transcends religious boundaries: a Christian monk whose heart beats in rhythm with the great bhakti saints.

For him, St. Francis is not a figure of another tradition but a brother on the same path — a soul who loved God so purely that his life became a living prayer.

NYC Kat at home in Gorvardhan Eco Village

Kat and Radhanath Swami and others

Radhanath Swami (born 7 December 1950 Richard Slavin, an Ashkenazy Jew) is a Gaudiya Vaishnava guru and author. He has been a Bhakti Yoga practitioner and a spiritual teacher for more than 50 years. He is the inspiration behind ISKCON's free midday meal for 1.2 million school kids across India, and he has been instrumental in founding the Bhaktivedanta Hospital in Mumbai. He works largely from Mumbai and travels extensively throughout Europe and America. In the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), he serves as a member of the Governing Body Commission. Steven J. Rosen described Radhanath Swami as a "saintly person respected by the mass of ISKCON devotees today."

__________________________

____________________

Tucker’s Corner

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple

The world never stops, but it does sometimes freeze. Postapocalyptic movies have taught us that, as they’ve presented all manner of wastelands strewn with the physical and cultural remnants of a past when the world was whole. Danny Boyle and Alex Garland’s 28 Days Later films (is that what we’re calling the series?) began with such images — of an empty London frozen at the moment of the zombie apocalypse — but last year’s 28 Years Later, reviving the franchise after nearly two decades, showed us how the survivors of that long-ago calamity tried to forge on in their own ways, combating the “rage virus” with twisted new societies and cults built from history’s detritus. Now, with 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, directed by Nia DaCosta, we witness a different kind of freeze: a psychological one. The minds of the people in this movie are also stuck in the past, even the ones who weren’t around to experience it.

The Bone Temple is in many ways a more conventional film than 28 Years Later; DaCosta thankfully doesn’t try to re-create the herky-jerky rhythms and mixed-media montages of Boyle’s picture. But it is a more psychologically acute effort. The earlier movie ended with a rather out-there finale that saw its 12-year-old protagonist, Spike (Alfie Williams), encounter a bizarre gang of blond-wigged, tracksuited, acrobatic zombie killers, all answering to the name of Jimmy. Now, we learn more about this little band of wannabe cretins and the twisted pseudo-satanic cult that their violent leader, Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell), has conjured around himself. Jimmy’s look is seemingly inspired by that of legendary British DJ and notorious sexual predator Jimmy Savile, whose crimes were mostly uncovered after his death in 2011. In this picture’s world, in other words, Savile (or at least some fictional version of him) would always have remained a beloved figure, his whole shtick there to be repurposed and exalted by The Bone Temple’s psychotic villain, whom we saw in the previous film’s early scenes as a young child surrounded by Teletubbies and religion at the time of the apocalypse. All that iconography, it seems, has conjoined and curdled in his mind to create the stunted-child monster he is in this movie’s present.

The somewhat fragmented, traveloguelike narrative of 28 Years Later is also replaced here by more fluid intercutting. While Spike struggles to fit in with the Jimmys’ murderous ways (it turns out they don’t kill just zombies), Dr. Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), who was introduced in the earlier film as a kindly, nutty hermit, tries to find ways to commune with the undead, dosing the massive alpha Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry), he of the infamously large zombie member, with morphine to see if that might pacify the beast. Kelson’s continuously growing temple, trees festooned with bones around a central tower of skulls, serves as a tribute to all the dead, including the zombies. In 28 Years Later’s most moving scenes, he spoke eloquently about trying to maintain one’s humanity and empathy amid such savagery by maintaining memories of the universality of death. That in order to do so he had to become something of a savage himself — a tough and crazy loner covered in red iodine and ready to do battle at a moment’s notice — was a supreme irony. Now, however, Kelson wants to see if his morphine concoction might bring Samson back to the person he once was. Does the infection destroy the mind, or is it more like a cloud, something that could conceivably be lifted? But Kelson doesn’t have enough morphine to make a real cure; mostly, he just seems to want a friend. He and the sedated Samson sit in the moonlight looking up at the stars. They even dance together. This is a very strange movie.

That the big zombie starts to show more humanity than the ostensibly non-zombified Jimmy Crystal should come as no surprise — genre films love that kind of humans-are-the-real-monsters reversal, and the previous entries in this series also touched on such ideas. What distinguishes The Bone Temple is that all these little paths into the characters’ inner lives start to cohere into a vision of human cruelty. In a brief flashback, we see Samson back when he was a happy young child riding the train with his parents; presumably, that was his infection point. In another moment, we see one of his victims through his eyes, and it looks like he’s basically attacking himself, as if trying to kill the thing he has become. Compare that with Jimmy Crystal’s desire to turn the kids he gathers into perverse photocopies of himself and the style he has adopted. Both extremes, each incapable of seeing others for what they are, result in immense barbarity.

The beauty of DaCosta’s film is that these particular ideas are worked in subtly, even though The Bone Temple itself is not what one might call subtle. In fact, it’s downright looney tunes, from Kelson’s occasional dance parties (powered by his collection of early-’80s LPs) to the screwy antics of the Jimmys to one spectacular extended climactic sequence of heavy-metal bravado that had my theater cheering and hollering. But even such scenes of crazed flamboyance fit into the film’s overall sense of a civilization stuck in time, of people mentally frozen at the moment of collapse. The only way to transcend and survive a dying world, it suggests, is to cut loose and find ways to be yourself.

________________________

Chuckles and Thoughts

Thoughts from Ralph

“On Listening”

To My Readers:

Transformation works best through sharing and dialogue. I am writing this essay to share my experience and to open a dialogue on listening. I told Dom to give my email to anyone who receives this article. I want to share three experiences that left me with a new way of understanding listening.

First Encounter: The Poetry Class

The first experience was a poetry class I have taken for over twenty years. I signed up because every time I read poetry it annoyed me. It was Greek to me. I thought I could fix this in one class. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

At the first meeting, we were all sitting together waiting for the teacher. One person sat with a book covering his face. I assumed he was a student who hadn’t done the reading. Someone finally said, “Where’s the teacher?” The man lowered the book and, without introduction, said, “Robert Frost, ‘Mending Wall,’ page fifty[1]one.”

I wanted to leave, but I was too embarrassed, so I decided to tough it out and never return. With no formalities, Tom read “The Mending Wall” and began asking questions. He offered no interpretations of his own. He just kept asking questions. At some point, I became riveted. I did not understand how Tom made poetry—and me—come alive.

After class I said, “Tom, can I tape this class?”

“Why?” he asked.

“Because no one should ever miss it.”

Over the years, Tom’s class transformed my life. For the first seven years, most of us kept retaking it again and again. During the pandemic, Tom asked seven of us if we wanted to continue virtually. Every invitation was accepted.

Something didn’t add up. Tom was an excellent teacher, but why such loyalty? Why did students take the class for decades? Why did an academic poetry class change my life when none of my college psychology courses did?

Tom wasn’t charismatic. He rarely offered his own views, especially in the early years. Yet the impact was undeniable. I began to suspect something else was at work.

Second Encounter: The Library and a Declaration

The second experience took place at the library where I write. I go there at least five days a week. I became casually friendly with one of the librarians, Erin.

One day we exchanged a quick hello, and I told a joke. Then something unexpected came out of my mouth: “Erin, I’m going to write a book of short stories called ‘Stories Toward a New Paradigm for Relationships.’”

I had no idea I was going to say that. I had even less idea how to write such a book. But I knew I couldn’t revoke the declaration. Erin had done nothing extraordinary. She was simply kind, professional, and present. Yet I felt compelled to honor what I had said.

I wrote the first story and sent it to my editor and friend. He replied, “We need to get you into your last book before it’s too late.” We did. At the last minute, my publisher included the story, “In Search of My Lost Sister.”

There was nothing Erin said that should have caused this. I began to suspect that listening itself—not words—was doing something. I started to think listening might be a phenomenon beyond sense perception.

Listening as Presence

In all three encounters, the impact far exceeded what physically occurred. A poetry class, a casual conversation, a promise—none of these should have had such power. As an architectural woodworker, I am pragmatic. There can be no error. Something had to be happening beyond sense perception. I spent years in communication courses, believing listening meant emptying myself for the other. I now believe that view is too simple. I strongly feel that listening exists as a presence beyond consciousness.

Heidegger said language is the house of Being. Heraclitus said opposites are unified. Listening and speaking are opposites. Could listening be another form of language—another way existence arises? That possibility excites me. I am also challenged by it.

I hope this essay gave you something. Please write to me or Dom if you want to share or continue the dialogue.

Ralph Indrisano

__________________

Six Word Stories

Suitcase packed. Ticket bought. Courage trembling.

AI interprets:

Those three short lines are doing a lot of emotional work — it’s a whole inner landscape compressed into a tiny space.

They signal a moment where the logistics are done but the feelings aren’t. The practical steps of leaving — packing, buying the ticket — are complete, which means there’s no turning back. But the body hasn’t caught up. “Courage trembling” tells you the author is standing right at the edge of a threshold: committed, but scared; ready, but shaking; propelled forward, but not yet steady.

It’s that fragile pause before a leap, when everything is technically in motion but the heart is still negotiating with itself. The tension comes from the contrast: the first two lines are decisive actions, the last is the truth underneath — bravery that’s real but wobbly.

Departure of the Folkestone Steamer (1869) by Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet - http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/59193.html?mulR=1569835165

_____________________________________

In the Mail

Tucker, expressing admiration for last issue:

You wrote some great stuff for it.

Lovely to read

__________________________________

Last Comment

Love this issue. We welcome the returns of contributions from Lisa and Kat. Lisa writes from her three-month tour to Europe, while Kat is taking an open-ended sojourn to GED to examine the life paths open to her, and is sharing some photographs of her life there. Love it.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!